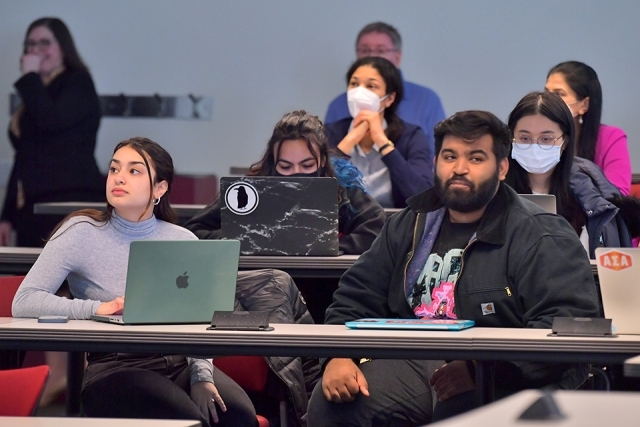

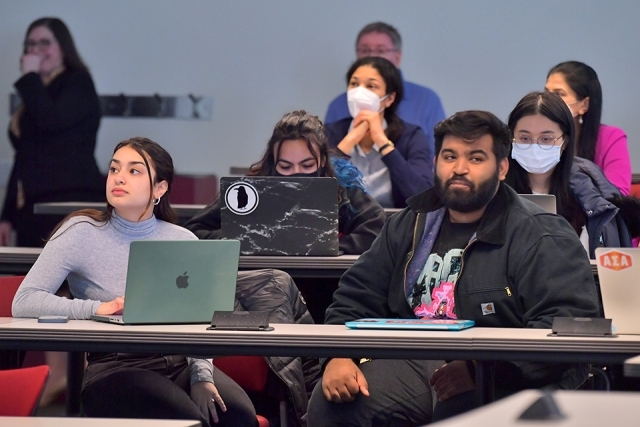

“What is art capable of?” That was the central question posed by Lisa Gail Collins, Ph.D., the 2022 Peter P. and Margaret A. D’Angelo Chair in the Humanities at St. John’s University, during the annual lecture held on April 4 in the D’Angelo Center on the Queens, NY, campus and on April 5 in the Kelleher Center on the Staten Island, NY, campus.

Peter P. D’Angelo ’78MBA, ’06HON and Margaret LaRosa D’Angelo ’70Ed established the Chair in 2007. It draws high-profile, multi- and cross-disciplinary visiting professors to St. John’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences for a semester of teaching and scholarly exchange.

Dr. Collins is a Professor of Art History, Africana Studies, and American Studies at Vassar College, and her talk, “Love Lies Here: Grief, a Quilt, and the Community of Gee’s Bend, Alabama,” focused primarily on the role of art—specifically quilt making—during the process of grief and healing. She stressed that art and art-making strengthen human bonds, build communities, open conversations, promote understanding, and tell stories.

A quilt fashioned by a mother and daughter in rural Alabama during the early 1940s to honor their late husband and father served as the primary lens through which Dr. Collins discussed the power art has to ease suffering and honor lost loved ones. “Their shared grief expressed itself in a material object whose conception, making, and use served the excruciating work of grieving a loved one,” she explained.

The quilt was created by Missouri Pettway, a resident of Gee’s Bend, AL, from the clothes of her deceased spouse, so she could constantly recall his presence whenever it was used. Two decades later, her daughter, Arlonzia Pettway, fashioned a similar quilt to honor her recently deceased husband, proving that this expression of love and loss was passed down from mother to daughter.

“Missouri Pettway drew on her skilled knowledge and intimate understanding of quilts and quilt making as a practice, a resource, and a source of comfort and created a wholly precious quilt. While newly suffering the loss of her husband, the quilt maker put her art and craft to exceedingly good use,” Dr. Collins observed.

Composed largely of her husband’s worn work clothes, Missouri Pettway’s hand-stitched quilt both implicitly and explicitly evoked ties between the practice of quilt making and the process of grieving, Dr. Collins noted, adding that it supported her grief and sustained her husband’s memory.

“I was deeply moved by Dr. Collins’s lecture about the history of a quilt made by a grieving spouse out of the worn, stained pieces of her deceased husband’s work clothes,” observed Gina M. Florio, Ph.D., Interim Dean and Associate Professor, Departments of Chemistry and Physics, St. John’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences.

“Dr. Collins connected the process of grieving with the creation of a quilt that served as an object for warmth, a cover of love, and a textile elegy.”

She added, “Dr. Collins’s work raises important questions about how grief works, what can be inherited and passed down from one generation to the next, and how art and the creative process help us to build community, understand our world, mourn, and even heal—the type of fundamental questions the humanities are uniquely positioned to address.”

“I found Dr. Collins’s lecture informative as well as emotionally moving,” noted David P. Bruno, a graduate student majoring in History. “It is fascinating that quilt making, something ostensibly thought of as mundane, can be so meaningful and complex. Dr. Collins did a fantastic job telling the story of Gee’s Bend and humanizing its residents. They are not just anonymous quilt makers, but people with interesting lives and stories. I am actually from Alabama and had not heard of the quilt’s existence before her lecture.”

Related News

The Institute for Catholic Schools and the School of Education Welcome the Inaugural Cohort of Future Catholic School Teachers Scholars

On February 5, eight St. John’s undergraduates—members of the inaugural cohort of the Future Catholic School Teachers Scholarship—joined the Institute for Catholic Schools (ICS) and The School of...

Q&A with Victor Visconti ’68ED, LEAD Honoree

Retired educator Victor Visconti ’68ED will be among several alumni honored by The School of Education (TSOE) at the 15th Annual Leaders in Education Awards Dinner (LEAD) on April 16 at the S tewart...

Q&A with Christopher E. Fisher, Psy.D. ’14M.S.Ed., LEAD Honoree

Christopher E. Fisher, Psy.D. ’14M.S.Ed., Licensed Clinical Psychologist and Director, Behavioral Health in Zucker Hillside Hospital, will be among several alumni honored by The School of Education...