“I’ve never lived in angrier times than right now.”

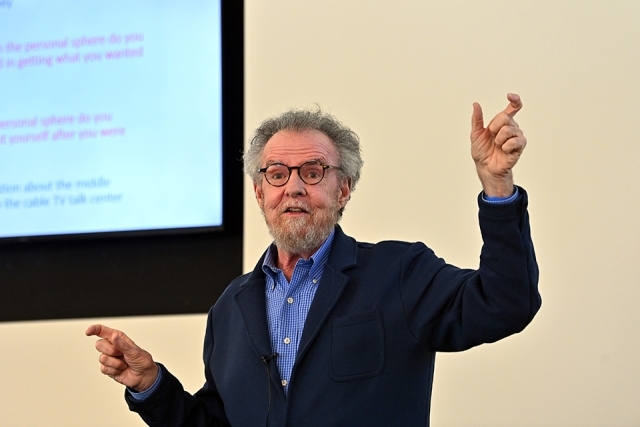

That was the observation made by Owen Flanagan, Ph.D., the 2023 Peter P. and Margaret A. D’Angelo Chair in the Humanities at St. John’s University, during the annual lecture held on April 3 in the D’Angelo Center on the Queens, NY, campus. Dr. Flanagan delivered the same lecture, “Our Angry Times: Is There a Way Out?,” on March 30 in the Kelleher Center on the Staten Island, NY, campus.

Peter P. D’Angelo ’78MBA, ’06HON and Margaret A. LaRosa D’Angelo ’70Ed, ’22HON established the Chair in 2007. It draws high-profile, multi- and cross-disciplinary visiting professors to St. John’s College of Liberal Arts and Sciences for a semester of teaching and scholarly exchange. For the last semester, Dr. Flanagan has served as a faculty member of the Department of Philosophy.

Dr. Flanagan, who is the James B. Duke Distinguished Professor of Philosophy Emeritus at Duke University, noted that he was an undergraduate from 1966 to 1970—some of the most tumultuous years in this country’s history. The times in which we now live eclipse those in terms of extremist points of view on both sides of the political spectrum.

“These were transformative times, but having lived through them I can also say they were times of great hope and idealism,” noted Dr. Flanagan. There was anger, he stressed, but it was couched in hope for the future.

Today the anger he witnesses is sloppy, vengeful, profane, and lacks reasoned discourse. Politics, on the left and the right, is performative and resentful.

“Children catch on to what the grown-ups are doing,” he stressed. Behaviors, he added, are contagious, and social media has only fanned the flames. “It provides an opportunity to react quickly to a system that gets provoked fairly easily.”

Dr. Flanagan detailed a trend that has developed since his youth that gives people license to express anger as part of their “authentic self.” He posited that a justification now exists for people to give rise to every emotion as they feel it without pause for reflection.

He posed the question, “Could liberal arts disciplines, scholarship, and teaching help find a way out of this morass?”

“I don’t have any hubris that we can change the world, but I think we can make some difference if we ourselves are articulate about the habits of heart and mind,” he responded.

Sometimes, Dr. Flanagan suggested, we must go outside our own cultural experience to find resources in other traditions that speak to the problem we wish to solve. “Otherwise, you’re in danger of being imprisoned by your own tradition.”

Anger has been studied in the Western tradition for many thousands of years. Dr. Flanagan said that Aristotle defined it as pain followed by a desire for revenge. “Anger is often followed by this desire for quick retribution.” Thomas Aquinas further explained that anger is a desire to make the other person suffer.

Years ago, Dr. Flanagan was invited with other philosophers to meet with the Dalai Lama to discuss destructive emotions. “Buddhists not only believe you should not act from anger, but that you should practice self-cultivation so that you do not experience anger.”

Culturally, Dr. Flanagan said, Americans often feel an urge to violence when provoked, whereas the Japanese and Belgians feel an urge to withdraw. “There are particularities to all cultures when it comes to anger,” he stressed.

Dr. Flanagan observed that there are zones of anger: toward friends and family, commercial relations, and the political sphere. He noted that in almost every interaction where anger has occurred very rarely does anyone get what they want. “We usually don’t come out of it feeling pretty good about ourselves.”

However, Dr. Flanagan stressed there are types of anger he feels are constructive and legitimate. “Recognition respect anger” doesn’t wish for payback, he explained. It expresses diminishment by virtue of race, ethnicity, or sexual preference. “I’ve been treated as less than you and I need to stand up. That is perfectly acceptable, and its aim is a change in attitude.” Righteous anger, he added, is directed toward dehumanizing social policies or structures that need to change.

“The idea that emotions are legitimate because they express who I am, and I’m entitled to them because I have experienced them, is a modern, narcissistic thought that can’t pass minimal inspection. Parents should never teach their children that they are entitled to all of their feelings. We educate desire and we educate emotions for the well-being of individuals, families, and communities.”

Related News

Q&A with Victor Visconti ’68ED, LEAD Honoree

Retired educator Victor Visconti ’68ED will be among several alumni honored by The School of Education (TSOE) at the 15th Annual Leaders in Education Awards Dinner (LEAD) on April 16 at the S tewart...

Q&A with Christopher E. Fisher, Psy.D. ’14M.S.Ed., LEAD Honoree

Christopher E. Fisher, Psy.D. ’14M.S.Ed., Licensed Clinical Psychologist and Director, Behavioral Health in Zucker Hillside Hospital, will be among several alumni honored by The School of Education...

Q&A with Darius Penikas ’08M.S.Ed., ’19Ed.D., LEAD Honoree

Darius Penikas ’08M.S.Ed., ’19Ed.D., Principal of Archbishop Molloy High School, will be among several alumni honored by The School of Education (SOE) at the 15th Annual Leaders in Education Awards...