How Alumna Sue Lucchi Became the Mets Steady Hand Behind the Scenes

For more than 30 years, Whitestone, NY, native Sue Lucchi ’94SVC has worked tirelessly backstage, first at Shea Stadium, then at Citi Field, to ensure ballpark operations for the New York Mets ran like a well-oiled machine. Now Senior Adviser for the club, Ms. Lucchi spent several years as Vice President of Ballpark Operations, overseeing everything from the efficient operation of stadium facilities to the team’s unique response to the 9/11 attacks.

“I was a huge Mets fan from day one,” she recalled. “All I wanted to do was work in baseball. I couldn’t play, so I had to find something else I could do in the game.”

Carving out a successful career in a field once dominated almost entirely by men, Ms. Lucchi is a pioneer in many ways. First in her family to graduate from college, she inherited a strong love of baseball from her family especially her grandmother.

“I was a huge Mets fan from day one,” she recalled. “All I wanted to do was work in baseball. I couldn’t play, so I had to find something else I could do in the game.”

Growing up in the shadow of Shea Stadium, Ms. Lucchi, a self-described homebody, did not want to venture far for college, so she enrolled at St. John’s University as an Athletic Administration (now Sport Management) major. While at St. John’s, the late Bernard P. Beglane, Dean and founder of the Athletic Administration program, helped her secure an internship with the Mets.

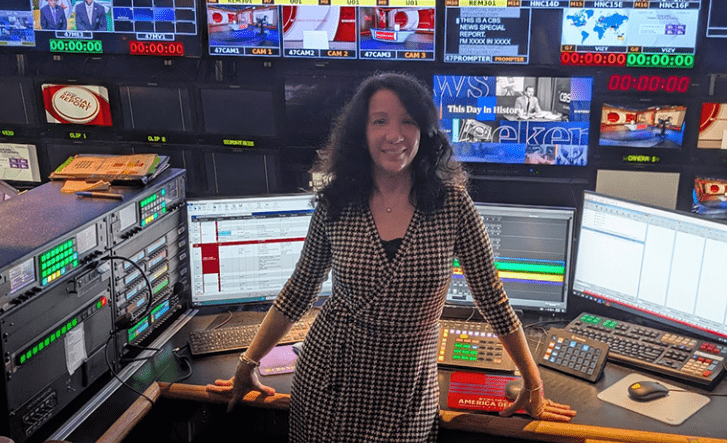

Initially, the internship was in the Media Relations department, but a bout of bronchitis forced her to miss her start date. “I went back to Dean Beglane, and he got me an internship in the Diamond Vision control room—and I never left,” she said.

Ms. Lucchi started on the last day of the season in 1993, not knowing she would spend her entire career with the Mets. “It was really hands-on training. I didn’t go to school for camera work or video or any of that stuff,” she recalled, noting that during the off-season she spent time assisting with on-camera interviews and video editing. She learned by doing. Upon graduation in 1994, the Mets hired her full time.

After a brief layoff during the infamous 1994–95 Major League Baseball strike, Ms. Lucchi resumed her role in the Scoreboard Department, but longed for a new challenge. “I was getting a little restless sitting in the same seat every day, watching every pitch. I kept score. I watched for changes so I could update the public address announcer. I would score the game so we’d have it for video footage when we needed it.”

She began interviewing with other local sports teams when Kevin McCarthy, Stadium Manager at the time, approached her. “He asked if I would be interested in an office manager position in Stadium Operations, which I knew nothing about, but I knew the ballpark.”

Since the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation managed the stadium, Ms. Lucchi did not oversee tradespeople such as electricians, but cultivated collegial relationships with them as they interfaced daily. As before, she learned on her feet.

“I moved quickly from office manager to stadium manager when my boss was promoted to director. I oversaw the grounds crew and the maintenance staff. At Shea, the Mets managed only the field, the front office, and the rooms used for our front office. The Parks Department managed everything else.”

Before long, Ms. Lucchi would face an unprecedented challenge for which none of her on-the-job training prepared her. On the morning of September 11, 2001, she was at Shea Stadium discussing logistics for a game between team sponsors. After the first plane struck the North Tower, the staff were glued to their television sets, she noted.

“After the second plane hit, we knew it wasn’t an accident,” she recalled.

Several staff members left the park to pick up their children from school. However, Ms. Lucchi stayed and was soon notified that the New York City Police Department (which housed a precinct within the stadium) wanted to use Shea as a triage center. “We started pulling out stretchers and piling them outside the gates.”

Sadly, it soon became apparent no wounded would be brought to the stadium, and Ms. Lucchi faced a new challenge. “The next day, we got another call that people were saying that Shea Stadium was a relief site where you could drop donations,” she said. To this day, Ms. Lucchi cannot recall any official announcement to that effect, “but people were not going to take no for an answer.

“My boss and I were like, ‘Okay, what do we do now?’ I put out a whiteboard that read, ‘Place donations at Gate C.’ That’s how it started,” she said. “The next thing we knew, the American Red Cross reached out wanting to provide a facility for the people who were working at Ground Zero. They showed up with cots for people to sleep. We turned one of the locker rooms into a showering area, where you could find a towel, toothbrush, toothpaste, soap, razor, and other essentials. Within two days, we were operating as a relief effort. People were hitchhiking all the way from Pennsylvania. They stayed at Shea and helped unload trucks. Restaurants were bringing food.”

The players were also involved. At that time, Ms. Lucchi’s relationships with the players intensified and she counts John Franco, former manager Bobby Valentine, and player Todd Zeile as very close friends.

“There was no, ‘Oh, that’s John Franco, let me get his autograph,’” she said. “It was, ‘There’s a guy named John Franco helping unload a truck.’ We were all one.”

Ms. Lucchi added, “We were all Americans there, helping and trying to do something because we were so lost. I wish that we had a sign-in sheet or had taken the time to get people’s names so we could stay in contact with them. Again, it was just people showing up wanting to help.”

Ms. Lucchi gradually rose through the ranks, eventually becoming Stadium Director, and simultaneously oversaw the dismantling of Shea Stadium and the transfer of operations to Citi Field. “I was the last person out of Shea Stadium,” she mused. “I used to ride my bike from one park to the other.”

When the Mets transitioned to Citi Field, they were now responsible for all the operations of the park. “I learned a lot,” Ms. Lucchi stressed. “That was eye-opening. Now I was doing contracts with electricians, engineers, plumbers, and painters, and then the full-time grounds crew, the part-time grounds crew, and the maintenance staff—and managing all of it from the field to the landscaping outside the ballpark. We oversaw all of it.”

In the intervening years, she also oversaw team relief efforts in response to Hurricane Sandy and helped initiate COVID-19 protocols established by Major League Baseball.

Today, Ms. Lucchi takes pride in navigating a successful career that began during an era of male domination. “Thank God I grew up following my brother around and hanging out with him. I was a tomboy. There were probably two or three times when I was 22 or 23 that I broke down because somebody said something to me and I ran into the bathroom, but I pushed through it.”

She added, “Ironically, I have worked with mostly men my entire career. I believe I’m well respected and have great relationships with them. It’s great that it’s not even a conversation anymore.”

Thanks to her time at St. John’s, Ms. Lucchi dedicated her entire career to date being loyal to one team, one community, and one mission—keeping the New York Mets home safe, accessible, and a shining example of a space that makes fans feel welcome.

However, she views her relationships with colleagues, many of whom became dear friends, as her greatest accomplishment. “I believe I was the only female head of operations [in Major League Baseball]. In my heart, I know that is an accomplishment. The relationships that I have built with my staff and how they feel about me is great.”