It was 1998, and Capt. Timothy Jaccard of the Nassau County (NY) Police Department (NCPD) found himself in the middle of a circumstance unimaginable to most people.

Called to a crime scene as a member of the NCPD’s Ambulance Medical Technician (AMT) team, he discovered the body of a dead infant in a garbage can. Not for the first or last time, he was moved with compassion for an innocent life cut short.

Sounding very much like St. Vincent de Paul—from whom St. John’s University draws its mission—Capt. Jaccard asked, “What must be done?”

“God works in strange ways,” Capt. Jaccard recalled. “That baby then sat in the morgue for three months. I stepped up and requested custody and the child was able to receive a proper burial.”

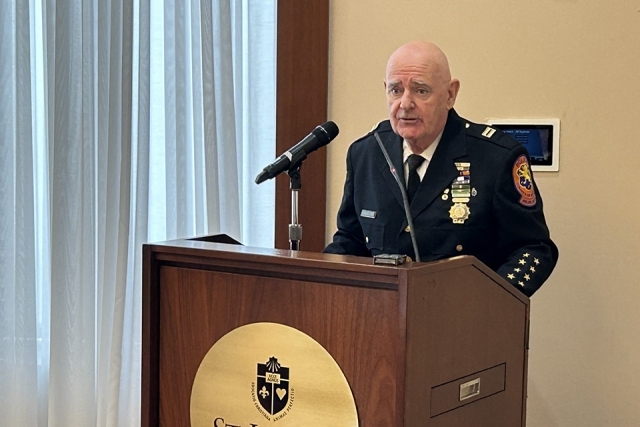

So began the AMT Children of Hope Baby Safe Haven Foundation and Capt. Jaccard’s national quest to provide a sanctuary for abandoned infants and those in danger of infanticide. The foundation, based in Mineola, NY, was honored during Founder’s Week with the University’s Frédéric Ozanam Award, given to an organization that blends service with effective and respectful concern for the poor or needy. Capt. Jaccard, President and Director of the foundation, was the guest speaker at the Founder’s Week lecture on September 26.

“Very early in his life as a priest, St. Vincent de Paul found a child who was abandoned in the streets of Paris and he picked up the child to be baptized,” said Rev. Patrick J. Griffin, C.M. ’13HON, Executive Director, Vincentian Center for Church and Society. “That’s why we wanted to honor Capt. Jaccard. He does something very close to our Vincentian heart.”

Capt. Jaccard’s initial goal was to bury every infant in Nassau County who was abandoned and died, or was killed. To bury the babies, however, Capt. Jaccard had to become their legal guardian. Since 1998, 222 of his deceased “children”—all given the surname Hope—have received a funeral at the Cemetery of the Holy Rood in Westbury, NY.

As Children of Hope grew, however, so did Capt. Jaccard’s thinking. Hoping to prevent the need for such funerals, he soon began pushing for what he called “safe-haven” laws that would allow women who have just given birth or a father to surrender their infant at a hospital, doctor’s office, firehouse, police station, or similar venue, no questions asked and without penalty.

“What is heartbreaking is over the years I have buried more than 200 babies,” Capt. Jaccard said. “We bury these children with honors. We have a ceremonial baptism where the babies are dressed in a tuxedo or baptismal gown and placed in a casket. We usually have 50 to 100 motorcycles that escort the babies from the funeral home to the church.”

By Capt. Jaccard’s account, the organization, and its 160 volunteers have saved more than 5,100 infants since 1998, including seven this year surrendered to him. Over the years, Capt. Jaccard has personally rescued more than 300 infants. His work has earned citations from the US Congress and the Permanent Observer Mission of the Holy See to the United Nations.

Mr. Jaccard joined the NCPD as a paramedic in 1973. Until 1998, he never imagined himself as a government lobbyist.

But in 1999, he found an ally in then-Texas Gov. George W. Bush. Pointing out that the city of Houston had more than a dozen infant abandonment deaths a year earlier, Capt. Jaccard petitioned the governor to make a safe-haven law a legislative priority. Texas that year adopted the Baby Moses Law, named after the biblical hero abandoned at birth. New York enacted its version of the law in 2000.

Other states followed suit. By 2008, the final year of Mr. Bush’s presidency, only Washington, DC, was without a safe-haven law.

“In 1998, the only governor willing to talk to me was the governor of Texas,” Capt. Jaccard recalled. “By 2008, the only place I could not get a law passed was the District of Columbia. I called the White House and on December 24—Christmas Eve—the president called me back and told me he signed a proclamation declaring Washington, DC, a safe-haven location. And now, it is the law there.”

“I like to say George W. Bush signed my first bill as a governor, and my last bill as president of the United States,” Capt. Jaccard added.

While safe-haven laws naturally protect infants, they also shield the surrendering parent from criminal prosecution for child endangerment, abandonment, or neglect. Most parents who surrender their children do so, Capt. Jaccard said, out of shame, financial inability, rape, or postpartum reactions.

Once a surrendered infant is considered medically stable, a local child welfare agency arranges for a foster home. In most cases, if the birth parents do not seek to regain custody or are deemed unfit, the child is placed for adoption. Therapy is available to those birth mothers who choose it.

Safe-haven laws are not without their critics, however. Parental anonymity and the lack of medical records and signed relinquishments from birth parents have created adoption issues. Critics have even said safe-haven laws encourage easy baby disposal.

To all those criticisms, Capt. Jaccard pointed to the number of infants rescued by the organization since that random day in 1998 when he discovered the dead child amid the rubbish. “It’s a good feeling to save these children,” he said.